‘London-think’ is prevalent amongst architects and many others in the property world, myself included. New housing in London seems to consist of one improbably extruded faux warehouse after another, wearing their ungainly fawn or coal-dusted brick overcoats like so many sulky teenagers.There’s nothing like some raw data to burst that bubble and remind everyone what ‘new housing supply’ in England actually consists of and who’s doing it. My wade through DCLG’s stats in Part 1 showed new housing delivery at a rate of about 150,000 homes a year. What I want to do in Part 2 is understand who is delivering England’s new homes, where, and what sort of homes they are.

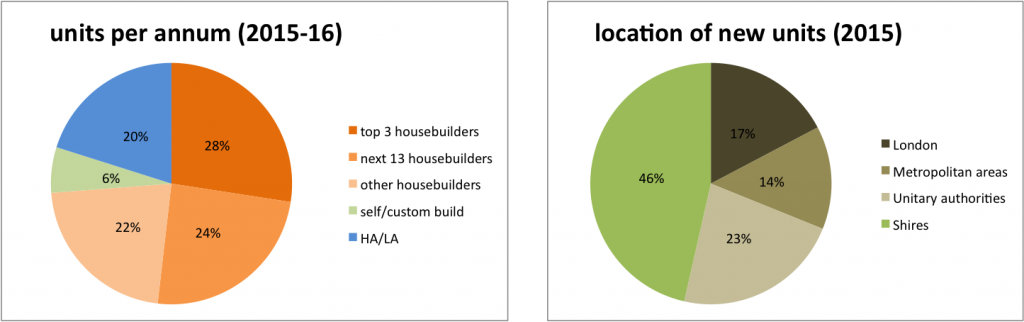

2015-16 was a bumper year with c. 164,000 new builds plus a record 35,000 conversions (either splitting up larger properties or changing use from say office to residential – left out in what follows). Unsurprisingly, the majority of homes are developed by private sector housebuilding organisations, with Barratt, Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey cleaning up almost 30% of delivery. And of course, most of it’s not in London: almost half is in ‘The Shires’ (as DCLG quaintly calls them). London’s stock (and that of the shires) is increasing at a rate of 0.8% per year whereas the Metro areas (Greater Manchester say) are lagging behind at only 0.45% increase per year.

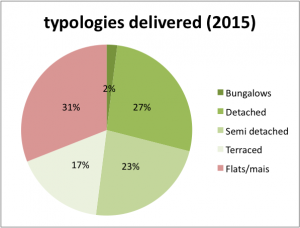

And what are we building? According to NHBC, it’s houses, making up about three quarters of output now (2016). To a London sensibility, this feels impossibly wasteful of land and materials, with the longed-for 2 metres of detachment giving rise to an absurd repetition of gable ends for the sake of status. But outside the metro-bubble, 30 dwellings per hectare and two cars per plot still rule, and the volume housebuilders have systematised that product to within an inch of its life.

And what are we building? According to NHBC, it’s houses, making up about three quarters of output now (2016). To a London sensibility, this feels impossibly wasteful of land and materials, with the longed-for 2 metres of detachment giving rise to an absurd repetition of gable ends for the sake of status. But outside the metro-bubble, 30 dwellings per hectare and two cars per plot still rule, and the volume housebuilders have systematised that product to within an inch of its life.

So there are two questions which I’d like to pose. First: if we want increased speed and volume of delivery of new homes in England, surely the serious R&D energy must be spent on houses? Not only are they the predominant type, they’re much easier to standardise and arrange on multiple odd-shaped sites. [Of course the volume players already do this: but let’s have far more templates please.] And second, are we really satisfied that the layout and amenities offered by the now-familiar suburban grafts are good enough? ‘Good’ does have to mean saleable and profitable of course. But good should also mean: attractive; serving the needs of diverse residents; solid and well-made; resource efficient; enabling community life; comfortable and flexible; playable – the list goes on. And before anyone points out how costly all that ‘nice stuff’ is, what is the long term cost of sidelining these aspirations? The final question therefore becomes whether it’s possible to enforce or at least encourage ‘good’ in a market where land is sold to the highest bidder, planning is weak, and people will buy anything. That’s for the next post.

A caveat: the datasources I used have a number of conflicts so I can’t vouch for the precision of my figures; but they’re probably about right.

PS the government launched Garden Villages and Towns (again?) today. Let’s not succumb to Garden-Wash: it’s worth remembering that Ebenezer Howard’s definition of a Garden City was 32,000 residents (about 12,000 homes) on 2,400 hectares (that’s a very low density of 5 homes per hectare). LB Southwark is about the same area with 10 times the number of homes. Just saying.

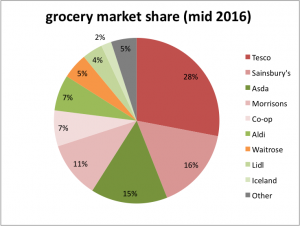

And finally I’ve compared food production and distribution with housebuilding before: there’s much more to add when I’ve got my thoughts straight. But in the mean time, here’s a starter for ten:

Data from Kantar Worldpanel