Scheme: Wohnstadt Carl Legien | City: Berlin | Developer: GEHAG | Architects: Bruno Taut + Franz Hillinger | Landscape architect: Bruno Taut (Other UNESCO estates: Ludwig Lesser; Legerecht Migge)

Cafe owner/info centre manager feedback: ‘It’s mostlly older people now, but others are catching on and these places are gentrifying and attracting new kinds of people’

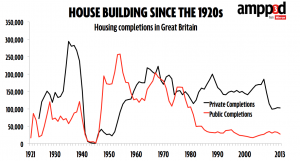

Just over 100 years ago, Berlin (in common with many European capitals) was in the grip of a similar housing crisis to today’s. In 1918, the war was over, private sector housebuilding had collapsed and people’s expectations of their home were greater than ever. Cities reacted in different ways to this pent-up demand, largely depending on finance availability. The UK’s house building boom (one of only two real ones in the last 150 years) was very much private sector led by a number of smaller actors: think small builders developing 1930s houses stretching for miles in London’s metroland. Mortgage finance and land availability were abundant, enabling individual families (not necessarily particularly wealthy ones) to buy their own discrete home and live the independent dream.  Affordable housing was built by councils under the Addison Acts, but this was a much smaller proportion of the total output. Unhealthy urban housing in the UK was already being tackled by Peabody and its ilk, but there was still a big mountain to climb to provide everyone (especially war veterans) with decent housing. Berlin, meanwhile, tackled its own housing shortage and quality using more state action and specially raised property taxation, kickstarted by the 1919 Weimar Constitution incorporating ‘house construction’ as a public function, guaranteeing ‘a healthy home for every German’. 20,000 new homes per year were built under this aegis in Berlin from 1924-31, with about 800 of these being the now UNESCO-listed modernist estates which circle the city. The after-effects of 1929’s downturn ended this run as state subsidies were abolished.

Affordable housing was built by councils under the Addison Acts, but this was a much smaller proportion of the total output. Unhealthy urban housing in the UK was already being tackled by Peabody and its ilk, but there was still a big mountain to climb to provide everyone (especially war veterans) with decent housing. Berlin, meanwhile, tackled its own housing shortage and quality using more state action and specially raised property taxation, kickstarted by the 1919 Weimar Constitution incorporating ‘house construction’ as a public function, guaranteeing ‘a healthy home for every German’. 20,000 new homes per year were built under this aegis in Berlin from 1924-31, with about 800 of these being the now UNESCO-listed modernist estates which circle the city. The after-effects of 1929’s downturn ended this run as state subsidies were abolished.

Berlin’s municipal building director (and architect), Martin Wagner, was a significant driving force in the building of the listed estates, not only in setting up the financing and emergency powers but also in ensuring that the housing and landscape was of the highest architectural quality. Garden City principles were taken very seriously in Germany, albeit that a city extension (or Garden Suburb) model was the preferred one rather than new settlements. As a result, and as a reaction to the slum conditions suffered by many in Berlin, the preferred initial typology was single or two storey houses with generous space standards and at low density. This changed as the estates progressed, going from 50 homes up to 150 homes per hectare in the later more urban (and expensive) locations. Whilst wash-houses, food growing and communal heating were welcome innovations at that time (in advance of new housing in Vienna and Amsterdam), mixed-use was not in favour and as a result, the estates lacked (and mostly still lack) adequate shops and commercial uses within the estate boundary.

Berlin’s municipal building director (and architect), Martin Wagner, was a significant driving force in the building of the listed estates, not only in setting up the financing and emergency powers but also in ensuring that the housing and landscape was of the highest architectural quality. Garden City principles were taken very seriously in Germany, albeit that a city extension (or Garden Suburb) model was the preferred one rather than new settlements. As a result, and as a reaction to the slum conditions suffered by many in Berlin, the preferred initial typology was single or two storey houses with generous space standards and at low density. This changed as the estates progressed, going from 50 homes up to 150 homes per hectare in the later more urban (and expensive) locations. Whilst wash-houses, food growing and communal heating were welcome innovations at that time (in advance of new housing in Vienna and Amsterdam), mixed-use was not in favour and as a result, the estates lacked (and mostly still lack) adequate shops and commercial uses within the estate boundary.

My favourite of the three estates I visited was the higher density Wohnstadt Carl Legien (WCL), masterplanned and largely designed for GEHAG by Bruno Taut, who was subsequently persecuted as a ‘cultural bolshevist’. He designed or masterplanned 10,000 of the new Berlin homes and had as his maxim ‘colour is zest for life’, visible in particular in the beautifully maintained windows at WCL with their different coloured frames and sub-frames. Blocks repeat and streetscapes are hard, but dignified: immaculate hedges provide privacy to ground floors and the sandy rendered elevations with their primary coloured windows are almost works of graphic design. The courtyards within are again simple to the point of harsh, but relieved by finely detailed loggias, consistently fertile window boxes (does someone give the residents lessons?) and finally, something unexpected: very loud and uplifting birdsong in the middle of the day.

My favourite of the three estates I visited was the higher density Wohnstadt Carl Legien (WCL), masterplanned and largely designed for GEHAG by Bruno Taut, who was subsequently persecuted as a ‘cultural bolshevist’. He designed or masterplanned 10,000 of the new Berlin homes and had as his maxim ‘colour is zest for life’, visible in particular in the beautifully maintained windows at WCL with their different coloured frames and sub-frames. Blocks repeat and streetscapes are hard, but dignified: immaculate hedges provide privacy to ground floors and the sandy rendered elevations with their primary coloured windows are almost works of graphic design. The courtyards within are again simple to the point of harsh, but relieved by finely detailed loggias, consistently fertile window boxes (does someone give the residents lessons?) and finally, something unexpected: very loud and uplifting birdsong in the middle of the day. (I am gradually learning how important trees are to urban life, for the multiple functions they perform.) I found Schillerpark a little colder: perhaps its more suburban location meant that the extreme quiet was not welcoming to a visitor. Siemensstadt was similarly suburban, but livelier, although the visitor centre manager remarked that all of the UNESCO estates were characterised by an older resident base and were ‘too quiet and isolated’ for his taste. A lively kindergarten at Schillerpark perhaps points to a new emerging clientele which might use the much-too-neat sandpits in the courtyards. Anyone can apply for a home on each one (they are not reserved for lower income households) but churn is low, though they do appear to be affordable, with two bed flats being advertised at about £700 per month including heating.

(I am gradually learning how important trees are to urban life, for the multiple functions they perform.) I found Schillerpark a little colder: perhaps its more suburban location meant that the extreme quiet was not welcoming to a visitor. Siemensstadt was similarly suburban, but livelier, although the visitor centre manager remarked that all of the UNESCO estates were characterised by an older resident base and were ‘too quiet and isolated’ for his taste. A lively kindergarten at Schillerpark perhaps points to a new emerging clientele which might use the much-too-neat sandpits in the courtyards. Anyone can apply for a home on each one (they are not reserved for lower income households) but churn is low, though they do appear to be affordable, with two bed flats being advertised at about £700 per month including heating.

WCL brought to mind the principle of repetition in housing. Peabody spent its first 20 years using one architect and one contractor, building its first 14 estates all around London using an evolving but very particular yellow brick aesthetic. Those blocks were and are recognisable, repeatable, and were cheaper due to bulk buying by Cubitts, who understood the product and knew how to cost and build it. It’s now an impossibility. Planners want ‘contextual materials’ (nobody knew or cared what this was in the 1860s), people have acquired rights of light, and small sites demand bespoke solutions. The indomitable Kelvin Campbell had a go, but are there just too many moving parts to make a standard block now? Could Local Authorities agree on a few ‘patterns’ for London’s bigger sites? Is there a fear of standardisation driven by 1960s monotony? For my money, collage can get tiresome and a bit of repetition and homogeneity (with some detail and craft) can create a sense of belonging.

WCL brought to mind the principle of repetition in housing. Peabody spent its first 20 years using one architect and one contractor, building its first 14 estates all around London using an evolving but very particular yellow brick aesthetic. Those blocks were and are recognisable, repeatable, and were cheaper due to bulk buying by Cubitts, who understood the product and knew how to cost and build it. It’s now an impossibility. Planners want ‘contextual materials’ (nobody knew or cared what this was in the 1860s), people have acquired rights of light, and small sites demand bespoke solutions. The indomitable Kelvin Campbell had a go, but are there just too many moving parts to make a standard block now? Could Local Authorities agree on a few ‘patterns’ for London’s bigger sites? Is there a fear of standardisation driven by 1960s monotony? For my money, collage can get tiresome and a bit of repetition and homogeneity (with some detail and craft) can create a sense of belonging.

PS: We caught the tube to the beach in Berlin. We put our bikes on it.