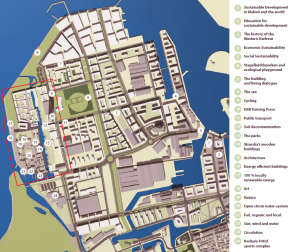

Scheme: Västra Hamnen | City: Malmö | Master Client: Malmö Stad | Developer: Various | Masterplan Architect: Klas Tham | Landscape Architect: Various

Cafe owner feedback: Me: It’s a bit empty – must be the holidays. Cafe Owner: It’s always like this…

Ambitions to make new housing developments eco-friendly often suffer through both technical and political challenge, as well as ‘residents behaving badly’. But they surely must be attempted, if northern Europeans are to set some kind of benchmark about resource conservation which others might follow. The Bo01 early housing phase at Västra Hamnen (Western Harbour) had grand environmental objectives (captured in a mandatory Quality Plan), with civic and design leadership to match; but 10 or so years on from that first phase of Malmö’s dockland reinvention, the outcomes bear some examination.

Ambitions to make new housing developments eco-friendly often suffer through both technical and political challenge, as well as ‘residents behaving badly’. But they surely must be attempted, if northern Europeans are to set some kind of benchmark about resource conservation which others might follow. The Bo01 early housing phase at Västra Hamnen (Western Harbour) had grand environmental objectives (captured in a mandatory Quality Plan), with civic and design leadership to match; but 10 or so years on from that first phase of Malmö’s dockland reinvention, the outcomes bear some examination.

Malmö’s harbour development was launched with an international housing exhibition Bo01 (Live 2001 or City of Tomorrow) which was also the first building phase. Aside from all of the technical requirements around energy and water use etc., the scheme’s masterplanner, Klas Tham (an acolyte of Ralph Erskine), rightly identified a broader theme:

Malmö’s harbour development was launched with an international housing exhibition Bo01 (Live 2001 or City of Tomorrow) which was also the first building phase. Aside from all of the technical requirements around energy and water use etc., the scheme’s masterplanner, Klas Tham (an acolyte of Ralph Erskine), rightly identified a broader theme:

“The urgent conversion of society to long term sustainability will only be possible when the sustainable alternative is regarded not only as the wisest, but also as the most attractive one…The prevailing quantitative standards for environmental sustainability, such as saving energy are necessary, but insufficient…It will not be until people’s aesthetic, emotional and social needs are also met that the sustainable society can be attained”

And here is the rub. The homes at Bo were so sought after that they are now attracting a higher price than the rest of Malmö; the clientele is wealthier than average and not ethnically as diverse as Malmö’s population. Bo01 was originally planned for a ratio of 0.7 cars per household, but today many homes have one or more luxury cars, for which there is no space (a shy plant-covered multi-storey has now been erected to cope with this). The district rented out electric cars to residents for two years but they were withdrawn due to under-subscription. (One fantastically-named campaign – ‘No Ridiculous Car Journeys’ – aimed to reward those who cycled more with a new bike.) Cycle lanes and special bus routes make the overall carriageways over-sized and there’s that under-populated feeling again which dogs young developments. Richer people seem to want to be warmer as well: the energy use was greater than expected. It seems wealthier people with fewer financial boundaries don’t prioritise being green. Following regular collaborative meetings with private sector partners, the city’s Quality Plan was ‘simplified’ in order to achieve improved viability as costs for the various green measures were high (as they always are). Tham must be a bit disappointed.

And here is the rub. The homes at Bo were so sought after that they are now attracting a higher price than the rest of Malmö; the clientele is wealthier than average and not ethnically as diverse as Malmö’s population. Bo01 was originally planned for a ratio of 0.7 cars per household, but today many homes have one or more luxury cars, for which there is no space (a shy plant-covered multi-storey has now been erected to cope with this). The district rented out electric cars to residents for two years but they were withdrawn due to under-subscription. (One fantastically-named campaign – ‘No Ridiculous Car Journeys’ – aimed to reward those who cycled more with a new bike.) Cycle lanes and special bus routes make the overall carriageways over-sized and there’s that under-populated feeling again which dogs young developments. Richer people seem to want to be warmer as well: the energy use was greater than expected. It seems wealthier people with fewer financial boundaries don’t prioritise being green. Following regular collaborative meetings with private sector partners, the city’s Quality Plan was ‘simplified’ in order to achieve improved viability as costs for the various green measures were high (as they always are). Tham must be a bit disappointed.

A note about the physical qualities of VH. There are some quite beautiful and sweet-smelling landscaped courtyards behind the perimeter blocks, and Tham’s streets in the Bo area (40 homes per hectare) are narrow, informal and villagey, creating street-based amenity space where the car is very much an intruder. Both of these environments work extremely well and have been personalised by their local communities (always a good sign). The built fabric is highly varied (a little too much for me) through the use of 25 architectural practices; it also varies substantially in quality over the years, the ‘tide-line’ of recession-driven architecture being quite visible! What’s also more than visible is the Calatrava Turning Torso tower, a truly awful, bullying object which far from advertising VH as the new go-ahead part of Malmö just shouts obnoxiously from every possible angle.

A note about the physical qualities of VH. There are some quite beautiful and sweet-smelling landscaped courtyards behind the perimeter blocks, and Tham’s streets in the Bo area (40 homes per hectare) are narrow, informal and villagey, creating street-based amenity space where the car is very much an intruder. Both of these environments work extremely well and have been personalised by their local communities (always a good sign). The built fabric is highly varied (a little too much for me) through the use of 25 architectural practices; it also varies substantially in quality over the years, the ‘tide-line’ of recession-driven architecture being quite visible! What’s also more than visible is the Calatrava Turning Torso tower, a truly awful, bullying object which far from advertising VH as the new go-ahead part of Malmö just shouts obnoxiously from every possible angle.  City leaders: stop! You don’t need one of these. Nothing wrong with tall, but by god it had better look good and be in the right place.

City leaders: stop! You don’t need one of these. Nothing wrong with tall, but by god it had better look good and be in the right place.

What is the right way to tackle a super-green project? Small schemes are in my view limited – I’ve always been skeptical about ‘demonstration houses’ because it’s surely in the higher density where real economies are found (e.g. using district heating), and the greater challenges e.g. of having not much useful roof for the floor space beneath. If a project is large however, there can then be too many moving parts and unpredictable results. (There’s also that awful possibility that the same mistake is made multiple times). Having toiled myself over the design of a small part of Greenwich Millennium Village, and also having supervised some post-occupancy research at Peabody’s BedZED, I know only too well how inspiring and yet frustrating the quest for true greenness is.

PS: watch a devastating 60 minute film called ‘Ecopolis China’ if you get the chance. It makes European efforts at being green look distinctly like shutting the stable door.