Scheme: Justuskwartier | City: Rotterdam | Owners: Woonstad Rotterdam |

Architect: Michiel Brinkman

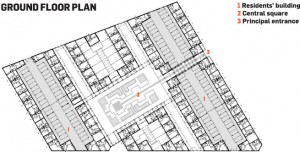

Scheme: Le Medi | City: Rotterdam | Funder/Concept: Hassani Idrissi |

Developer: Era Contour + Havensteder | Architect: Geurst & Schulze + Korteknie Stuhlmacher | Landscape Architect: Geurst & Schulze + DS&V

Resident feedback: (Justuskwartier) ‘It’s quiet, there are gates which close the area at 8pm. But it’s expensive!’ [£600/month…]

Resident feedback: (Le Medi) ‘We can close the gates – no cars – great for the kids to play – they don’t need to be supervised’

Gates enclosing estates have a long but controversial history. In London’s Peabody estates in the 19th century, gates and fences ensured that only the ‘working poor’ gained entrance to their superior courtyard environments whilst the rest could only dream. The war effort meant that those barriers were melted down – quite literally – and the Peabody estates have almost all remained un-gated to this day, a state of play which can cause tension, but which also speaks of a permeable and public sensibility. The 1980s famously brought a new spate of gated estates to London; subsequent studies have shown that gating housing makes its residents more fearful rather than less, as they learn to percieve the outside world as a threat. Clearly gates also create less permeability for all other citizens, as well as ensuring a divided, ‘us and them’ ground plane.  In the Netherlands and other parts of northern Europe, I see very few fences and gates. Dutch visitors to London recently played ‘spot the fence type’ with me – and we counted at least 20 before I felt embarrassed at how many ways the Brits had managed to cut themselves off from other people. But can a boundary of sorts sometimes have advantages?

In the Netherlands and other parts of northern Europe, I see very few fences and gates. Dutch visitors to London recently played ‘spot the fence type’ with me – and we counted at least 20 before I felt embarrassed at how many ways the Brits had managed to cut themselves off from other people. But can a boundary of sorts sometimes have advantages?

At Le Medi, gates are closed to traffic and the residents can choose whether or not to leave the pedestrian gates open. The resident I met mentioned the sense of safety/autonomy for playing children as his number one plus point for his home, citing also the neighbours and community as being ‘gezellig‘. T here are many cultural and architectural layers to Le Medi which I haven’t room for here, but it manages to combine a north African aesthetic with the special Dutch way of appropriating and defining one’s notional front garden with big plants, bikes and public seating. I confess that I do enjoy walking around car-free residential environments, but I do also like the notion that I can, as a member of the public, walk through there unimpeded.

here are many cultural and architectural layers to Le Medi which I haven’t room for here, but it manages to combine a north African aesthetic with the special Dutch way of appropriating and defining one’s notional front garden with big plants, bikes and public seating. I confess that I do enjoy walking around car-free residential environments, but I do also like the notion that I can, as a member of the public, walk through there unimpeded.

Justuskwartier is a 1922 estate on the city edge of Rotterdam, innovative in its day for pioneering deck access as well as communal facilities such as baths and a heating system. It has recently had a make-over by its housing association owners to restore it back to its original brickwork finish and include new raised beds.  One of the new features was large boundary gates, something remarked on by the resident I met, who approved of this security, which is implemented at 8pm. He also mentioned that his flat was expensive, and I realised that the attractive 20s architecture was now fetching a premium, having previously probably been seen as ‘not market’ housing. Surrounding Justuskwartier is far inferior new affordable housing which does not live up to the craft and detail of its illustrious, philanthropy-styled neighbour. I suspect that the gates are sadly now dividing the more affluent in the ‘heritage buildings’ from the newer lower income residents beyond.

One of the new features was large boundary gates, something remarked on by the resident I met, who approved of this security, which is implemented at 8pm. He also mentioned that his flat was expensive, and I realised that the attractive 20s architecture was now fetching a premium, having previously probably been seen as ‘not market’ housing. Surrounding Justuskwartier is far inferior new affordable housing which does not live up to the craft and detail of its illustrious, philanthropy-styled neighbour. I suspect that the gates are sadly now dividing the more affluent in the ‘heritage buildings’ from the newer lower income residents beyond.

Thanks to Joost Kok from Macreanor Lavington for pointing me to both of these schemes.